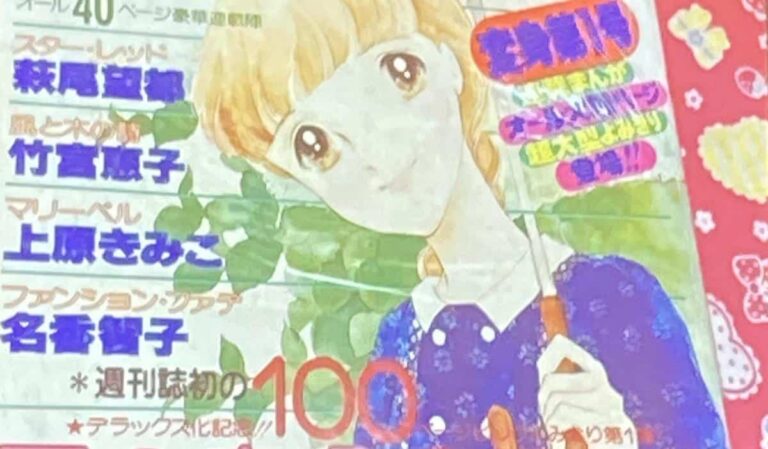

The photos below were taken from slides from Evan Mint’s “Manga Magazine Mania” panel at Anime NYC 2024. Mint himself reportedly found some of these images in online shops and auction sites.

Many of the panels at this year’s Anime NYC were about anime premieres and upcoming licenses. But if you look closely, there were some exciting exceptions hosted not by corporations but by hard-working individuals. Take the case of Evan Minto. Like everyone else, he hosted the obligatory industry panel for Azuki. But then he hosted the latest installment of Anime Burger Time, a panel that exclusively featured funny clips of anime characters eating burgers. I found his third panel the most informative: Manga Magazine Mania, about the history of manga magazine publishing in Japan. Unfortunately, that time slot was 15 minutes shorter than Minto had anticipated, but it still had a ton of interesting details.

In the U.S., manga is typically distributed through comic books or specialized manga apps. But in Japan, manga magazines survive. These magazines are published weekly, biweekly, or monthly. (Mint noted that some companies stagger their publication schedules to have a wider range of manga each month.) Individual chapters from these magazines are compiled and published as complete collections, or “tankobon.” These are then rebranded and sold overseas.

Manga elements

Japanese manga magazine readers view manga differently from international readers in several important ways. For example, manga magazine paper is notoriously poor quality; it’s cheap, recycled, and often bears traces of previous works. The cliché that manga is something to read on the train and then promptly throw in the trash is unfounded. On the other hand, the margins of these magazines often contain author comments and character biographies for new readers, which are cut out of the tankon versions.

Other differences are due to the way magazines are published. For example, magazines promote related products and unearth undiscovered talent. They also contain advertisements, which for historians provide instant proof that the magazine is set in a particular time and place. Covers vary depending on the readership and may feature popular characters, caricatures, or even swimsuit photos. Tables of contents can also be a source of contention. Fans of Weekly Shonen Jump, in particular, will pore over the table of contents of their chosen magazine like tea leaves to find out how their favorite series is doing in the magazine’s rigorous reader polls.

The invention of manga

English-speaking readers may be familiar with demographics in marketing in publishing. Japanese magazines are typically categorized as for boys, girls, young men, women, and children. On the surface, it’s simple, but long-time manga readers know that the reality is different. For example, the shoujo manga parody Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun is published in the boys’ web magazine Gangan Online. The strongest influence on manga serialization is not demographics, but the editorial standards of each magazine.

Of course, as Minto says, today’s manga magazines were not born, they were invented. He traced the origins of manga back to the early 20th century. It didn’t start with ukiyo-e or Choju Jinbutsu Giga, but with the publication of American and European comics in Japan. (Manga industry luminaries Zach Davison and Erica Friedman told a similar story during their manga history panel at Anime NYC; they recommended Ike Exner’s book, The Origins of Comics and Manga: A Revisionist History, for further reading.) Japanese artists were inspired by the comic supplements of newspapers in these countries to create their own comics. One example, jiji manga, began publication in 1902. But these supplements featured political cartoons and comic serials, not the “story manga” that Japan would later become famous for.

Boys’ Manga

Slowly, demographics began to take shape. As in South Korea, government censors initially restricted content and encouraged the publication of children’s magazines. An early example was Monthly Shonen Club, published by Kodansha in 1914. The magazine contained articles, photographs, and (eventually) longer comic strips than newspaper comics. It was also printed in color, making it very different from today’s comics.

Over the next few decades, publishers like Akita Shoten and Shueisha would publish their own monthly boys’ magazines, but it was Kodansha’s Manga Shonen, published by former Shonen Club editor Kato Kenichi, that really took manga to the forefront. Some of Manga Shonen’s most popular series included Inoue Kazuo’s Batkid (now available in English) and Tezuka Osamu’s Jungle Emperor. Manga Shonen also accepted submissions from readers, another step towards modern manga as we know it.

Intense competition

Magazine serializations faced competition from rental comics. In Osaka, akachanhon, or “red books” published on cheap paper, were published. Tezuka Osamu’s Shin Takarajima was one of the most successful books, and launched his career as a popular manga artist. As Ryan Holmberg wrote in Comics Journal, other comics were more diverse in style and content. The Osaka market later sowed the seeds of the gekiga movement, or “alternative comics” aimed at adults.

Meanwhile, Kodansha launched Weekly Shonen Magazine on March 17, 1959. On the same day, Shogakukan launched Weekly Shonen Sunday. Just as Tezuka’s works were influenced by movies, these magazines borrowed their stories from radio drama series. Weekly magazines quickly gave way to monthly magazines. Even Kodansha’s girls’ magazine Nakayoshi switched from a monthly to a weekly. Shueisha responded with its girls’ magazine Weekly Margaret. The competition was fierce.

Comics for the people

Into this crowded field emerged Shueisha’s Weekly Shonen Jump. Though Jump would go on to become the most successful manga magazine of all time, it initially failed to attract the prestigious artists that other publications employed. As a result, the magazine’s editors embraced amateur work, offered to represent less experienced artists as agents, and used reader surveys to gauge what readers were most interested in. These practices determined the magazine’s later strengths (popular young artists contractually bound to Shonen Jump’s pages) and weaknesses (formulaic story structures, a willingness to cancel up-and-coming series rather than give them the opportunity to grow and evolve).

During the protest era of the 1960s and 70s, Japanese students embraced manga as their medium of choice. Children’s pulp comics became a counterculture. Ashita no Joe, for example, embodied the hopes and frustrations of its readers at the time, as did Sanpei Shirato’s politically radical ninja manga Kamui Densetsu, published in Garo, the once great alternative manga magazine. Meanwhile, Nagai Go’s 1968 series Harenchi Gakuen proved that manga doesn’t necessarily have to be respectable or avant-garde, it can just be vulgar.

The birth of seinen manga

Eventually, the Japanese economy boomed and readers were able to buy the magazines and books they wanted instead of relying on rentals. This caused the rental manga market to collapse. Artists jumped on the bandwagon and into the new adult-oriented magazines, seinen magazines, starting with Futabasha’s Manga Action in 1967. Some of the more well-known series include Monkey Punch’s Lupin III and Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima’s Lone Wolf and Cub.

Manga continued to diversify to reach as wide an audience as possible: children started with Doraemon in CoroCoro Comic, then moved to Shonen Sunday, before moving on to adult works by Tezuka and Koike, and even other magazines focusing on pachinko and mahjong.

June Events

At the same time, a market for experimental magazines was also emerging. One such magazine was the boys’ love manga magazine JUNE, founded by Sagawa Toshihiko and edited by manga artist Takemiya Keiko and novelist Kurimoto Kaoru (under the pen name Nakajima Azusa). The magazine had a huge influence on a certain readership, and works with the same aesthetic sensibility are still sometimes referred to as “JUNE stuff.”

Another important step was the birth of women’s manga. Originally called reddy comi or “lady comics,” the early magazines in this genre published erotic manga aimed at adult women. These works filled a reader’s need for explicit content that girls’ manga magazines refused to provide. They also provided a space for female artists who were tired of working within the editorial constraints of early girls’ magazines.

Four Heavenly Kings

However, the four most popular magazines in Japan were all aimed at boys: Shonen Magazine, Shonen Sunday, Shonen Jump, and Shonen Champion. The series published in these magazines were designed from the beginning to be collected into tankobon volumes later. Competition for sales and top artists was fierce. One way to balance things out was through TV anime adaptations. Although manga once saw anime as a source of competition, it later became its most powerful promotional tool.

Kodansha, in particular, became famous for a strategy they called “media mix.” Rather than adapting a manga series into an anime or vice versa, publishers would simultaneously build anime and manga versions of a particular concept. Sailor Moon is a great example of this. The manga series was published in Nakayoshi in 1991 before the anime was released in 1992, but both the manga and anime were planned at the same time. The release schedule created a synergy that led to Sailor Moon becoming ubiquitous throughout the ’90s, regardless of age.

Slime appears!

In the late 1990s, manga sales declined. Magazines for all ages were discontinued, and in 1997, Shonen Magazine took over from Jump’s number one spot. This was in part due to the end of several popular Jump comics during this period, such as Dragon Ball and Slam Dunk. But manga also faced competition from a new medium: video games. Enix, publishers of the smash role-playing game Dragon Quest, launched their own imprint called Gangan Comics in 1991. The magazine featured many popular series (such as the ever-popular Fullmetal Alchemist) as well as stories about related video games.

Despite manga’s popularity overseas, it’s undeniable that the market has changed. Tankobon sales surpassed manga sales in 2005. Digital manga revenues surpassed print magazines in 2016 and tankobon revenues in 2017. Many of Shonen Jump’s most popular series run online on Jump+, rather than in print magazines. Vertical scrolling webtoons, especially in Korea, have also been very successful. This doesn’t mean paper is outdated. Artists know that physical media offers opportunities for print and texture that can’t be replicated digitally. But manga has never valued the quality of paper as a medium.

Why do magazines exist?

Minto concluded the panel with a suggestion for those interested in Japanese manga magazines: Digital magazines are available on the Japanese website BookWalker. Kinokuniya, a Japanese bookstore chain with several locations across the United States, also sells manga magazines in its magazine section.

The American publishing industry has experimented in the past with English versions of Shonen Jump and comprehensive anthologies such as Shojo Beat and Raijin Comics. Unfortunately, these no longer exist. However, in the fall of 2024, Starfruit Books plans to launch an indie manga magazine called Comic Bright. If this is successful, we may see similar efforts from other American manga publishers. For this to happen, however, readers will need to prove that the format is viable.

The manga itself

Mint brought along some paper manga magazines, including old issues of the seinen magazine Big Comic, the joshi magazine Feel Young, and the experimental Garo. Seeing these magazines in person, he was struck by how quickly digital comics have replaced the physical packaging and branding of the past few decades. As a result, one might think that the prices of old issues would skyrocket. But as Mint points out, back issues of manga remain surprisingly affordable. The magazines were merely a delivery vehicle; it’s the manga itself that counts.

Like this:

Like Loading…