In what universe is Freddy Krueger worse than Donald Trump?

OK, what I meant to say is, “Why are we not only still telling horror stories, but why is there a genuine resurgence right now? In a timeline that’s clearly the worst by ever definable metric, why is horror still this profoundly important lens/perspective? Because laugh as I may about Trumpy-Wumpy, the man’s the monstrous personification of a shared grief, misery, and violence that’s been brewing for decades.

It’s a question I’ve posed (directly and otherwise) to many comics writers/artists, but few answers have been as satisfying as the one offered up by Ryan Parrott.

“If you look at any horror, the nice thing about it is there’s usually rules,” Parrott said during a recent Zoom call. “I grew up on the ‘90s slasher movies…Chucky and Ghostface. Literally, there are rules in Scream to survive that movie. And the funny part is in the real world, there are no rules. And if anything we’ve learned this year, it’s that the rules you thought would be there to protect you are not there, and they are all smoke and mirrors. So maybe there’s an element of fairness in the horror genre that appeals to people in that sense of…usually the hero still vanquishes the villain and you survive.”

And just like any rules-based system in the world, anyone who follows it will get their just desserts. Generally speaking, of course.

“In almost every horror story, the person starts off in this one place, and by going through this horrible experience, they are better for it,” Parrott said. “They end up on the other side changed, and that even though this was the worst thing that ever happened to them, it ultimately made them a better person or they learned something or they grew in some way.”

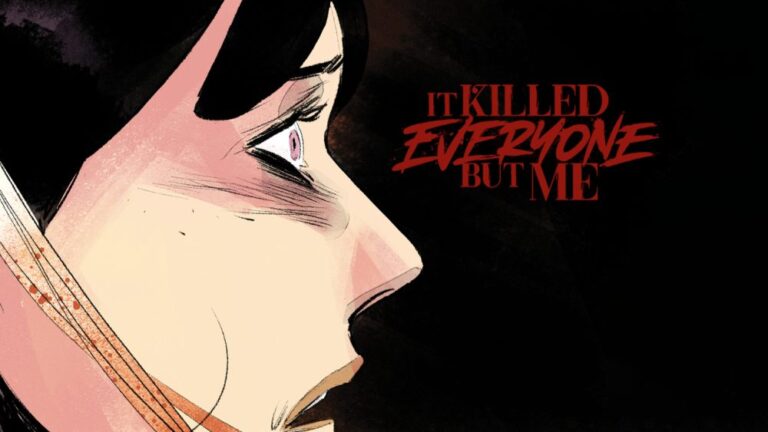

It’s this very dynamic that rests at the heart of Parrott’s latest comic, the slasher horror drama It Killed Everyone But Me (alongside artist Letizia Cadonici, colorist Alessandro Santoro, and letterer Taylor Esposito). We follow Sutton Reed, who as a teenager in 1996 became “the sole survivor of the legendary Riverton Massacre.” Now, some 30 years later, Sutton must delve back into her bloody past (and reacquaint herself with the evil creature known as The Heathen) if she wants to help save two missing teens. It’s like I Know What You Did Last Summer meets Drop Dead Fred — and you’ll see why oh-so shortly.

On Grief, Trauma, and Horror’s Essence

In some ways, It Killed Everyone But Me was written as a reaction to more recent horror titles. Parrott said that most of these horror stories (even his own) seem to be about “grief and trauma.” So, he penned a story that both leaned into and subverted some of that emotionality.

“This story is about somebody literally burying their trauma away and ignoring it and then having to dig it up 30 years later and deal with it,” Parrott said. “So I do think there’s something that’s really activating about that. This story is, in some ways, a cautionary tale about how you can’t just pretend something didn’t happen and be OK. It will affect your life in ways that you weren’t even aware of. It’s not until you acknowledge it and you face it that you’re able to accept it that you are able to actually overpower it.”

Main cover by Jorge Corona and Sarah Stern. Courtesy of Mad Cave Studios.

To an extent, personal empowerment in the very DNA of modern horror. It’s what makes the genre so egalitarian in the first place.

“The villain represents the physical personification of this horrible event,” Parrott said. “We just turned him into vampires and monsters and all that stuff. And it’s about, ‘OK, taking them on, becoming the person you’re meant to be and beating them,’ there is something really great about that. I think there’s something cool about the genre that allows fair play, weirdly enough.”

The issue, then, is that many horror stories aren’t doing more with empowerment. As much as we’re tackling grief, some standouts aren’t responding to these sentiments in ways that feel relatable.

“I really enjoyed the (2021’s Halloween Kills),” Parrott said. “But what frustrated me a little bit about it was it was so clear that we’ve all gotten to this idea of Sarah Connor and Laurie Strode, both are the exact same thing, right? It’s like they had this horrible thing happen, it held onto them, they bunkered down literally and locked themselves away and never escaped that moment. That’s not usually how people work.”

“She is like a great white shark — she just keeps moving forward.”

So, as a response to that, Parrott and the team opted for a sharp counter to this “model” — someone who hasn’t overcome a damn thing and is stumbling along a half-lived life.

“I love the idea of going the opposite direction with somebody who goes through this horrible experience and then you pick up with them 20, 30 years later and they seem fine,” Parrott said. “They’re doing great. They have this business and their stuff together. And the whole ‘fake it till you make it’ is exactly right. I looked at it with this idea that person was like, ‘I refuse to be a victim and I’m going to show the world. So I’m going to push against that so hard that I’m going to pretend that I am fine.’ But when you dig a little bit deeper, you realize (Sutton) doesn’t have a great relationship with her kid. She obviously lost her husband and she’s brutal to some of her coworkers. She is like a great white shark — she just keeps moving forward.”

Horror in The Pandemic Era

It’s an idea that feels very relevant in our “post-COVID” world. We’ve all gotten used to the idea of accepting terrible things and trying our best to ignore them outright or contextualize them in a way that we can get by for yet another day. But while Parrott said that “Superman or Batman never dealt with COVID,” he very much wanted Sutton to engage with some of these overarching themes and feelings.

“I don’t know if you’ve watched the show The Pitt, which I loved,” Parrott said. “I didn’t think people would want to watch a show about doctors dealing with COVID. I didn’t think that’s something we’re all going to go, ‘Hey, that’ll be fun.’ But I loved that the show was like, ‘Hey, we’re still dealing with it. And some of us haven’t even come to grips with the fact that we are still dealing with this horrible thing when we were on the front lines.’ And they found a really elegant way of actually going, ‘Hey, some people were made stronger for this and we had people go into the medical field because of it. But also some people had to watch people they love die and they have never quite come to grips with that.’”

In part, Sutton’s journey across It Killed Everyone But Me is spurred on by Ian, a journalist looking into her story and trying to cover the latest crop of missing teens. It’s that “relationship” that encapsulates some of these key ideas about grief and surviving day-to-day.

“It’s Ian coming to her and saying, ‘Hey, there’s another set of kids getting killed and dealing with this.’ She has to basically either acknowledge it or not,” Parrott said. “It’s that thing of ‘I can’t do that again, but I’m also not heartless enough to ignore it.’ And so this story is about her having to literally dig up that trauma and go face-to-face with it when it’s trying to destroy her again.”

Going back to the whole idea of “horror’s sense of fairness,” a lot of It Killed Everyone But Me emphasizes Sutton’s whole back-and-forth: When is trauma truly resolved, and how do you use it as existential “kindling” when it’s all said and done?

“With Freddy Krueger or Jason, how do you beat these things? They live by their own rules, right? How do you destroy something that exists in dreams? If you did beat it and you buried it, but you know it’s never dead, it’s just sitting there,” Parrott said. “And then when you bring it back up, and now you have to talk to this thing that hates you and wants to destroy you. It’s the ultimate victim facing her victimizer. Can you take that and wield it for good? Can you take that and make the world better? And I thought that would be an interesting choice. That’s ultimately what the story ends up being about, a little bit of Nightmare on Elm Street meets The Silence of the Lambs.”

Parrott added, “I guess the larger question is, did you truly beat something if you didn’t learn from it? We get into marriages that don’t work out, or have other situations and jobs, and then you get out of it. Did you learn your lesson from the thing that happened? Or, are you just acting again and doing the same thing over and over again? I think a lot of us survive things, but we don’t actually evolve from them. There’s a difference between survival and learning and evolving, right? She survived this thing, but did she actually learn from it or is she just existing in it with blinders on?”

“The horror genre is alive and well. Every year I think we can’t come up with something new, and then something new comes up.”

Even Sutton’s choice of job (mostly middling real estate agent) reflects this huge idea about how she sees and interacts with her client base.

“I actually imagined her a lot like Annette Bening from American Beauty,” Parrott said. “There’s very similar moments from the scenes in the montage, where (Sutton’s) like, ‘Look how tropical this place is.’ I just always thought that was such a great thing of somebody who was looking at the worst situation and trying to flip it. That’s a lot of what she’s doing, right? People are coming there and going, ‘This is what I want my life to be.’ And she’s like, ‘Well, this is what it is. It could be like this if you just looked at it this way.’”

Appeasing a Smarter, Hungrier Audience

As mentioned above, this is all about getting people to reconsider horror to an extent. That while the genre is clearly having its day in the sun (moonlight?), the development and proliferation of the genre still raises some interesting questions. You can’t just make the same things over again, and you need to realize any new story’s place in some ever-evolving canon.

“Someone will make something tomorrow that’ll basically overwrite what I’m about to say,” Parrott said. “But I do think that almost every genre goes through different stages. There’s the classic genre, which is the beginning, then you get into the subversive version of it. And then you have an end version, where it starts to eat itself. I don’t think horror will ever be in the ‘eat itself’ version because there’s still so much. We were just talking about Weapons off camera. The horror genre is alive and well. Every year I think we can’t come up with something new, and then something new comes up.”

Variant cover by Trevor Henderson. Courtesy of Mad Cave Studios.

However, we are, as Parrott noted, at the point where creators have to be subversive about horror (and fans/audiences should expect as much). When everyone’s a horror fan, it makes the “medium” all that more complicated and demanding.

“Your audience is aware and has watched so many versions,” Parrott said. “You’ve got to give them something that takes the concept that they know and flips it on its head a little bit. I don’t know if we can do another straight movie where there’s 12 kids at a camp or a cabin and they’re getting picked off by a mass killer. You’ve got to give them something a little bit different.”

At one point, Parrott made a reference to sneaking pills in treats when his dog was once sick. (Fret not, unlike some horror tales, this pup got better.) It’s a perfectly wonder analogy for how genre should operate nowadays.

“I do think there’s something fun about trying to find a classic situation and then take it and then flip it and have the audience have to process it in real time,” Parrott said. “I always think there’s a lot of movies that do that I think are really, really great about that. Genre is something where it’s a vocabulary with an audience, and you can use as a shorthand to get to some really interesting conversations.”

Tackling The “Survivor’s Generation”

And “talking” with your audience means recognizing aspects of them and their media consumption. It’s here that we get at this idea of It Killed Everyone But Me as being (per a press release) “a slasher film for the survivor’s generation.” Parrott has an important story from his own adolescence that really gets to the heart of that concept.

“There was a shooting when I was in junior high,” Parrott said. “And I remember going back to that school and somebody slamming a door too fast and everybody jumping. I remember what that felt like. There’s a generation of kids who have survived and gone through shelter in place drills. They’ve gone through this idea of going to school and knowing that at any moment this could happen and it could happen anywhere. When I said the slasher for the survivor generation, there’s an awareness of that.”

“Why we hide the things that we hide, and how when sometimes we don’t want to talk about things, that thing can boil up inside of you. It will eventually poison you.”

It’s about drilling deeper until you find this core that is, at least partially, novel enough to entice an audience. But mostly it’s about being more cutting and personal than any similar projects.

“So coupling that idea of going through that constant trauma and a place that’s supposed to be safe with this idea of taking the genre and saying something different with it, I definitely think you have to just give an audience something a little bit more than that,” Parrott said. “It can’t be a traditional thing. I think you have to say something about it. And so that’s what I wanted this to be. I wanted it to be a little bit of about…it’s a therapy session hidden in horror. I’ve done therapy, and it’s very helpful, but it can be a very scary thing to face your own inadequacies.”

And when Parrott mentions therapy, he’s almost nearly literal.

“The next two issues are about Sutton and the Heathen and the idea of those two people in a room together,” Parrott said. “He is literally the personification of her trauma, and so how how does your trauma come at you and how do you dodge it?”

Parrott added, “But there’s also putting chains down people’s throats and gutting them. At the core of it, I do feel like you have to be willing and want to say something and be open and vulnerable about it. I tried to be vulnerable about why people do the things they do, why we hide the things that we hide, and how when sometimes we don’t want to talk about things, that thing can boil up inside of you. It will eventually poison you.”

Courtesy of Mad Cave Studios.

It’s never about being less afraid — it’s about knowing that sometimes there’s bigger stakes than your own fears.

“It all really does come down to a sort of a tête-à-tête between The Heathen and Sutton, and this idea of…the only way out is through,” Parrott said. “The only way that she is going to be able to help (the young teen) Mason and stop this from happening to other people is if she really acknowledges and really comes to grips with what happened to her and admits some deep secrets.”

Making New Friends is Scary

To really nail the Sutton-Heathen dynamic, it’s not just about emphasizing their deep history and thematic richness. No, it starts with the physical, and the whole team was dedicated to fostering a specific vibe for the book’s villain (if you’re keen on that kind of simplification).

“I didn’t want him to stand in the corner with his hands like this and be a vampire or the faceless man in the suit everybody uses,” Parrott said. “There’s something more interesting to me about making him a little more playful. He likes to play with this food. He’s almost a little Puck-ish. But he could also bite your face off if you let down your guard. I was also like, ‘I don’t want to make him ugly. I want to make him beautiful in a weird way.’ Let’s make him a little bit more dangerous looking so he’s just not this thing that’s going to sit in the corner and scare you.”

Parrott added, “Plus, we just liked the idea that if he had been buried for 30 years, he would just be stretching. If you’ve ever come home, and your dog’s been sleeping for 30 minutes, the minute you walk in the door he’s running around.”

It also helps that It Killed Everyone But Me has a “connection” to another beloved horror series, as Cadonici was a regular artist on House of Slaughter. It’s a connection that Parrott is more than happy to lean into (to an extent, of course) not only from a visual standpoint but as another series that’s focused on evolution and subversion within horror.

“I would be lying if I was a comic book writer and I didn’t know anything about Something is Killing The Children. James (Tynion IV) is a good friend,” Parrot said. “He’s somebody who really does a wonderful job of taking the elements of a genre that you know and finding a new way in and finding a way to talk about really great things. Things that also bend the medium in ways that are fantastic. I would be lucky if I’m in the same pool as him. We both are enjoying some of the same elements and the same ways of subverting that stuff.”

But Cadonici wasn’t just taking House of Slaughter and translating it outright. For one, her work often focused on other vital elements beyond, say, the outright terror of it all.

“It’s not about the gore with her. It’s about the hauntingness,” Parrott said. “It’s about the side looks and the feeling. There’s an energy and a dread in her art that I really, really love.”

Parrott added, “It was really fun to let (Cadonici) go with it. Like, just having her design some of the characters and going back with Heathen four or five times was really fun. I think this would be a very different book if she hadn’t come on there. I think the story would have changed a lot, too. I definitely leaned into some of the more traumatic elements and emotional stuff with Sutton because of the way that she depicted her.”

“I’m thinking about someone’s tongue getting pulled out of their mouth.”

And that emphasis (the emotional over the gory) isn’t just a preference but it instead gets at the very core of what we’ve been talking about so far. It’s about never letting anything (blood, genre tropes, other people’s work, etc.) get in the way of the heart of the story itself.

“I like gore and mayhem as much as the next ‘90s kid,” Parrott said. “But I was thinking about this with the Hellraiser ‘genre.’ Clive (Barker)’s an incredible writer. I love some of his actual, non-horror stuff. But some of the lengths with which he goes with body horror sometimes, I have to turn my head away just because it’s so graphic and so disturbing. When that happens, I’m no longer thinking about the metaphor of the story that you’re talking about. I’m thinking about someone’s tongue getting pulled out of their mouth.”

Or, to put it in cooking terms (for some strange reason): “Maybe less is more because I think it can become so overpowering. Gore is a spice; you don’t want to throw too much paprika into your chicken. You’re not going to be able to eat it.”

There’s still some gore, of course — maybe even stuff that Parrott himself might somehow regret.

“We really do play a little bit with the gore,” Parrott said. “I won’t lie that the Heathen has some very dark ways that he dispatches people. I will say that some of the most fun and scary things I’ve ever written are through him. And I’m like, ‘I hope that’s not me.’ I hope that’s not something from my heart because he really enjoys messing with you.’”

The Art of Proper Gore and Terror

But you don’t need all those gallons of blood when you’ve got Cadonici involved. She’s not just a master of creating these deeply haunted visuals. She’s also very much about using sparse, random details to extend a character’s prowess. It’s those small touches that have such a massive impact on the characters and themes.

“I remember (Cadonici) was like, ‘I want her to wear this red coat.’ And I was like, ‘What a cool thing.’ I never thought about the fact of having characters that have signature elements,” Parrott said. “She (also) had the idea of the silhouette for The Heathen being this crooked man. There was something about (Sutton) being so traumatic that she’s like, ‘I’m wearing a red coat and I’m fine.’ She’s a target, right? She’s not trying to hide herself. If you’ve gone through something, you want to withdraw, and she’s doing the opposite.”

Once the physical/visual empowered the story, that’s when things really took off. To once again revisit the Sutton-Heathen “relationship” (it really is the most layered and intriguing aspect of It Killed Everyone But Me), it’s a dynamic that’s benefited massively from the playful, almost sensuous elements that have come to define this book.

“It’s not love as much as it might be predatory dominance,” Parrott said. “I think their relationship, as the series progresses, is a more evolved one.”

“And if you want to believe him, you are welcome to. But also remember that he is a liar and a murderer. So buyer beware.”

Parrott went as far as to compare Heathen to Ghostface than, say, Jason or Freddy. Sure, the strong silent type or the pun-wielding psycho are fun, but ol’ Ghostface knew how to get in deep with his victims (and, in many ways, foster a similar level of intimacy with the audience).

“Will I give you pieces that explain who he is and why he is? Yes, I will,” Parrott said of Heathen. “There’s going to definitely be moments where…he’s somebody who likes to talk, and I love talking villains. If you make him face something that he doesn’t want to face, he will turn on you as quickly. He is a caged animal in a lot of ways. He represents a very scary part of her life that she’s not ready to deal with. But I think as time progresses, and the more she has to engage with it, I think her feelings about what he is and what he means to her and what he has turned her into will evolve.”

Courtesy of Mad Cave Studios.

The Heathen is happy to mess with Sutton and the audience alike, and the creative team have positioned him as this force that’s hard to deny — even when your whole body is telling you to run away.

“There are moments where he is going to tell you, and he will allude to, what he is, and what all of the supernatural elements in this world are and why they exist,” Parrott said. “And if you want to believe him, you are welcome to. But also remember that he is a liar and a murderer. So buyer beware.”

What kind of monster is The Heathen, then? Why the kind who is much more like Hannibal Lecter just with all the worst supernatural powers ever.

“He does have this thing that I really love in the story, where he really enjoys watching that last moment when someone realizes that this is the end of their story,” Parrott said. “And like this idea that, yes, this is it – this is the end. He savors that like a fine wine.”

The Scares Run Deeper Still

The only person who can’t run away, then, is Sutton. But while their relationship may move beyond “victim and perpetrator,” there’s also limitations involved. It’s a dynamic that’s about respecting her journey as both a character in a story and a horror protagonist in a different sort of terrifying journey.

“…not all the monsters in this world are supernatural.”

Let’s turn toward a famous comedian to better understand this component.

“Stephen Colbert said something about this thing – she doesn’t have to love the worst thing that ever happened to her, but she has to accept the worst thing,” Parrott said. “I think that’s the difference. It’s not going to be, ‘Thank God, you killed all my friends. I’m a stronger person.’ But I think you have to accept the fact that this thing did happen and that because of it you became a certain type of thing. She hasn’t even accepted that this thing happened. She doesn’t want to acknowledge it. When she finally does, she might be able to unlock something in herself that might make her a better person.”

Parrott even referenced his own experiences, with the similarity driving home the intensity of Sutton’s process as well as what happens when horror is used to disarm and rebuild us as people.

“I have been accused of having ADHD many times, and for a really long time, I was like, ‘That’s ridiculous,’” Parrott said. “Then I started looking into how people deal with ADHD and I was like, ‘Oh, those things actually work on it.’ So it wasn’t until I was even willing to entertain the idea that it was there that I was actually able to use those tools to become better and combat them.”

There’s certainly more to the story than Sutton and The Heathen (even if, once again, it’s such a perfect encapsulation of the way It Killed Everyone But Me pushes horror forward on bloody knees). Parrot said there’s a monologue in issue #4 where we “find out why Ian is so connected to this story that I really liked because I think it gives you a sense that not all the monsters in this world are supernatural.” And Heathen’s not even the only spooky threat, either.

“We obviously get to ideas that this is a larger world,” Parrott said. “Like, there’s another villain in the story called The Stain that you’ll get to learn about. That person has a relationship with The Heathen, and there’s a larger world behind-the-scenes you get a glimpse of and how and where all of those monsters came from. That’s all connected thematically.”

Courtesy of Mad Cave Studios.

However, there’s no escaping (much like Jason stomping through the woods) the notion of growth through suffering. You can find something positive in the wreckage of your old life if you have the gumption to sort through it all. Or, sometimes the worst monsters in our lives are the ones with the most important/undeniable lessons. There’s even the notion that we can’t know if we’ll survive a thing, but we just have to act accordingly.

It’s a process and journey Parrott has committed to — truly and deeply.

“I think if I went up against Chucky, I could just probably get up on high furniture and have a better chance,” Parrott said when asked about a horror film bad guy he thinks he could vanquish. “But I don’t think I ever really totally appreciated Saw. The coolest thing about that first movie is the fact that she survives and she thanks him for it. And I was like, ‘That’s amazing.’ Maybe my own Saw, where I’d have to eat my own intestines. And I’m like, ‘Let’s do it. I’ll be better on the other side.’”